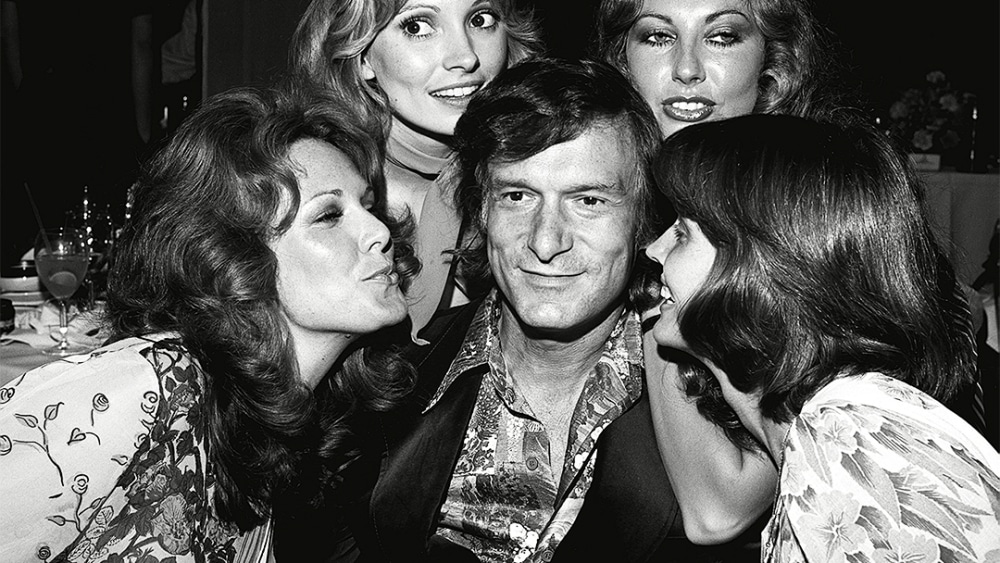

The death of Playboy mogul Hugh Hefner in September drew accolades as well as critiques from, shall we say, some rather strange bedfellows. Some on the left praised his support for civil rights (that is, he objectified black women too) and his more infamous role in the sexual revolution. From the right, an editorial in The Federalist  bizarrely misnamed his sense of personal entitlement as joie de vivre and his exploitation of women as a celebration of complementarity, and excused all the ugly vulgarity of his extreme sexual liberalism because it was all in the name of entrepreneurship – which goes to show just how large a sacred cow that word is within American society. Ironically, it also points to why his critics are correct, both about the grave harm done to women by his self-serving hedonism, and about the social corrosiveness of his capitalistic exploitation of human vanity and libido. In a way it’s not surprising that praise and critique of Hefner cut across the usual political categories, because he built his life and legacy directly on the intersection between the sexual liberalism of the left and the economic liberalism of the right.

bizarrely misnamed his sense of personal entitlement as joie de vivre and his exploitation of women as a celebration of complementarity, and excused all the ugly vulgarity of his extreme sexual liberalism because it was all in the name of entrepreneurship – which goes to show just how large a sacred cow that word is within American society. Ironically, it also points to why his critics are correct, both about the grave harm done to women by his self-serving hedonism, and about the social corrosiveness of his capitalistic exploitation of human vanity and libido. In a way it’s not surprising that praise and critique of Hefner cut across the usual political categories, because he built his life and legacy directly on the intersection between the sexual liberalism of the left and the economic liberalism of the right.

In fact, the same thing could be said of much of the entertainment industry more generally, which is why the reactions to Hefner have continued relevance to the ongoing fallout from recent revelations about Harvey Weinstein, whose pattern of sexual harassment and assault is being more unambiguously (and justly) condemned. Journalists, commentators and even a few A-list actors are calling this a sea change, a watershed moment, and as clichéd as that sounds, it is taking on the feel of one as more women are being emboldened to speak, more men are being implicated, and a bigger picture is emerging of a pervasive culture of sexual misconduct. And it’s in this bigger picture that the crucial question lies, which will determine whether a true and lasting sea change is possible: can the culture itself, embedded as it is in individualism and possessiveness which distort our view of the human person, be taken to task?

On one level, of course, it is a welcome sign that sexual harassment has become less accepted, and that a growing number of men in the business, news, and entertaining professions are speaking up against it. But for it to be truly uprooted from its foundations, what’s needed is not merely for more heads to roll, but a whole cultural paradigm shift: away from the reduction of human beings to isolated objects whose claim on a particular set of rights is perceived in direct competition with our own, and away from the reduction of human interactions to mere transactions in which the only ethical standard is consent.

This reductionistic paradigm is the unwritten contract, so to speak, between the left and right sides of the neoliberal coin that dominates American political currency. Nathan Schneider nailed their convergence spectacularly in a recent essay for America Magazine, writing,

If alien observers were to conduct an analysis of the contemporary left’s sexual politics, I suspect they would find close affinities with a doctrine the left is supposed to be organizing itself against: neoliberalism.

This is the ideology by which individual choice and discrete transactions should govern all. Everything is a potential commodity. Shared agreements, shared culture, shared solidarity are regarded as threats to freedom, especially in economic life. Everyone’s job is to get what they can get away with. Neoliberalism neutralizes values and communities by rendering them as merely private concerns.

“There is no such thing as society,” as Margaret Thatcher notoriously put it. “There are individual men and women, and there are families.” It can feel on the left nowadays that there is no such thing as families, either.

This leftist neoliberalism is less apparent at the level of language, where there are lots of shared norms about the appropriate ways to speak about gender and sex; these rules represent an admirable, though sometimes off-putting, effort to resist exclusion of any kind. But I am more concerned about the language governing acts.

A term the alien observers would hear a lot is “consent.” This is the ritual byword that justifies and enables. In lieu of shared judgments about what is or is not proper sexuality, participants must only consent to whatever particular thing they are doing, like a kind of verbal contract. Interestingly, this is almost the same defense that union-busting corporations use to justify paying terrible wages or that banks use to avoid accountability for ruining customers’ lives. It was all in the contractual fine print. Therefore, it is free consent.

Consent, like any neoliberal choice, is a slippery thing. Leftists know better than most that workers do not take lousy jobs because they prefer them to better ones. They do it because they have no real choice.

Certainly, as Schneider also points out, consent is necessary as a bare minimum standard. Sex without consent is rape, and work without consent is slavery. But a bare minimum standard is not enough: taken by itself, it is invariably too minimal, and thus far too easily taken advantage of in predatory ways. If a woman consents to providing sexual favors to keep her job, or to signing a non-disclosure agreement shielding her abuser from the consequences of his actions, or if an employee consents to hazardous working conditions or to an unjust wage that can’t feed his or her family, this is a situation of exploitation – whether sexual, economic, or both – and in that sense is little better than rape or slavery.

If the systems that allow such situations are to change, it will require a massive disillusionment with the two great lies on which empires of exploitation are built: that sexual liberalism is liberating, and that economic liberalism is moral. Far from being conducive to freedom as we’re often told, this double-sided ideology enslaves. The despotic idol is not easily dethroned, but perhaps with some of its ugliest damage so publicly exposed, we may yet begin to see cracks in its foundations.

Julia Smucker is a French interpreter and translator currently living in Portland, Maine. She has contributed to several print and online publications and serves on the board of the Consistent Life Network. She holds an MA in Systematics from Saint John’s School of Theology in Collegeville, Minnesota, where her classmates dubbed her the Anti-Dichotomy Queen.

This article was originally posted on Vox Nova.

Leave A Comment